Welcome to this ninth reflection on In Fragments — this week exploring Space Suit, a ritual to witness the cremation of my mother. You can view it here:

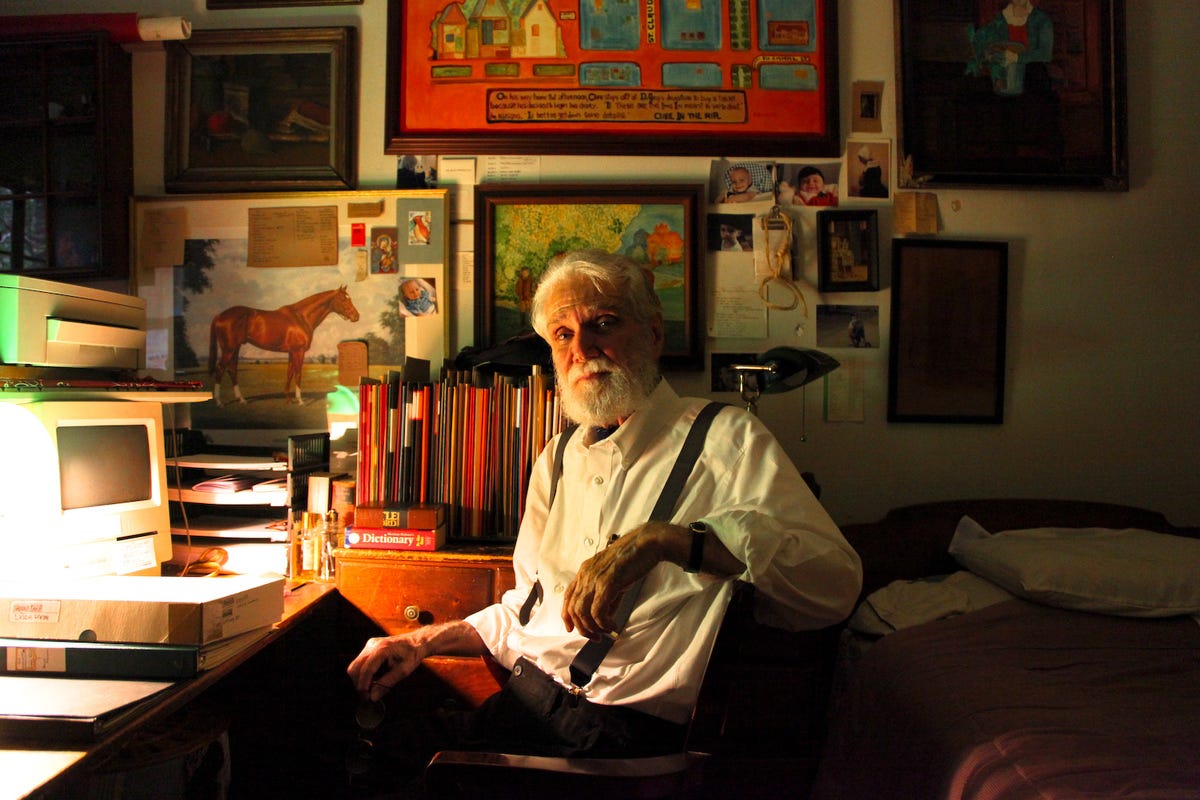

A couple weeks before he died, my fourth grade teacher, Ronald Bazarini, invited me to visit the small New York City apartment where he lived with his wife, Corinna, of more than fifty years. Baz, as everyone called him, sat scrunched up on his twin-sized bed, his frail body wrapped in an old woolen blanket, with his colorful collection of artwork and fedoras hanging on the walls around him. As we talked, I sat a few feet away from his bed, nestled in his sturdy wooden desk chair, where he’d written plays about Chekhov and a book called Boys, a collection of anecdotes from his decades of teaching at St. Bernard’s School in Manhattan. At a lull in the conversation, he smiled and gently asked me: Do you want me to tell you how I think it is?

I nodded quietly, and he slowly began: This planet we’re on is like a spaceship. It’s spinning every day around its own axis. It’s spinning every year around the sun. And the whole solar system is spinning in the galaxy, which itself is spinning in the universe. These bodies we have, they’re like our spacesuits. They allow us to be here, eat the food, breathe the air, and experience our lives. They’re our spacesuits, but they’re not really us. What we truly are I can’t say, and where we go next I don’t know, but I’m convinced that we do not end with our bodies. My own body’s served me well, and I’m grateful for it. But now it’s tired and worn out, and it’s almost time for me to set it aside. I have no qualms about that. I feel ready. Only perhaps a little sadness for the people left behind who I know are likely to miss me.

He went on to tell me what he felt was the secret to being a good teacher — to bring your whole self to class each day, and to meet your students as you truly are, rather than trying to wear the mask of “teacher” and play a particular role of what you think a teacher should be. When you’re honest and real, your students can sense that, and it makes them trust you more, which makes them more open to learning.

He told me how he came to hold this view, going back to his experience as a young playwright doing his MFA at Yale. It was summer vacation, and he was living in the countryside with his young wife, Corinna. In the mornings, he worked on his plays, while Corinna worked in the garden. Each day around noon, they met in the kitchen for lunch, and Baz would lie down on the large kitchen table, looking up at the ceiling, while Corinna finished preparing their meal. One day, lying on the table, he suddenly burst into tears, without knowing why. Corinna came to his side, put her hand on his arm, and said softly: “Baz, don’t lose heart.”

“I was trying to write these plays,” he told me, “that tackled big important themes of life and death. But my writing was always coming up short, so I felt like a failure. That day as I lay on the table and wept, I realized that I needed to take a different approach. I realized that I’d been trying to make the audience go WOW! when in fact, I needed to make the audience go wow…” I asked him what he meant by these two kinds of “wows,” and he smiled and said it again: “I was trying to make the audience go WOW! (as he raised his open palms and leaned back in his bed with a look of amazement) — when instead, I needed to make the audience go wow… (as he slowly leaned forward towards me with a look of focused fascination).

“You see,” he said, “I was trying to impress the audience with my brilliance through these big complicated ideas — but I didn’t have the wisdom really to explain these ideas, so my plays were falling flat. What I realized I had to do instead was to live in the question, to invite the audience up onto the stage with me, to participate in the not-knowing, so that we could explore the question together.”

“When you make a WOW!, you try to stun people with the power of spectacle, and maybe they feel amazed for a while — but then after a few days, they’ve forgotten the experience entirely, because there wasn’t any space for them to make it their own.”

“When you make a wow…, it’s more like planting a seed in the heart of each person, and maybe it takes a little time for that seed to sprout, but when it does, it can live inside them for years, becoming a permanent part of how they see the world.”

Or as another fine teacher, Kenya Hara, once put it:

As long as the message is pure, the more gently it is spoken, the more forcefully it will reverberate into the world’s receptive places, as a penetrating whisper.

The day my mother died, I thought of these final teachings of Baz — that perhaps what she was doing that day was stepping out of her bodily spacesuit, but that the way for me to navigate this strange experience was simply to “live in its question” without trying to collapse or define it.

This ninth ritual of In Fragments documents my mother’s cremation, which took place three days later at a local funeral parlor. The music that accompanies the film is the prelude to Richard Wagner’s final opera, Parsifal, about the knights who guard the Holy Grail — the same music that was playing in my mother’s bedroom on the afternoon that she died, as my sister and I lay with her in bed, while the setting winter sun was filling up her room with warm golden light.

Every death, of course, is also a new beginning. As my mother’s spirit began its onward journey into the unknown, a new era of life began on our land: one that would come to involve ritual, architecture, renovation, construction, children, hospitality, learning, and the arts. In my own world, alongside the grief and confusion, I also felt a new sense of possibility: a new era of life beyond the witnessing gaze of my mother.

As Baz, in his careful and exquisite handwriting, for more than fifteen years, would always sign off his annual Christmas cards to our family:

Kiss the children,

— Jonathan

P.S. The recording of the “Stoa Session” that I did last Friday is now online — exploring In Fragments, Life Art, and the “technology” of ritual. In a way, it was my own kind of foray into becoming a teacher. You can view it here:

P.P.S. Last week we lost a true shining light, the architect Christopher Alexander, one of my heroes, and a masterful teacher of the timeless.

Here are some glimpses into his world…

Patterns in Architecture — his famous 1996 lecture to computer scientists that birthed the “design patterns” movement:

Spaces for the Soul — a colorful documentary about his work and ideas, from when he was in his passionate prime:

Message from Christopher Alexander — a Japanese TV clip from 2011, shortly after the stroke that greatly diminished his abilities to communicate, if not to feel:

Here is Alexander’s definition of “life,” from his magnum opus, The Nature of Order:

What we call “life” is a general condition that exists in every part of space: brick, stone, grass, river, painting, building, daffodil, human being, forest, city. Each center gets its life, always, from the fact that it is helping to support and enliven some larger center — the center becomes precious because of it. Thus, life itself is a recursive effect which occurs in space. It can only be understood recursively as the mutual intensification of life by life.

May he, Baz, and my mother be gathering somewhere together, conversing in peace.

What a beautiful way to start the day. Your writing is glorious. That’s the best word I have right now for it. And also that photo of Baz made me want to create a studio for myself again. I’ve had them before, but not for a long time. To be surrounded by the images and objects that bring meaning to your wor and remind you of who you are. wow.

I remember well your story on Baz when you first published it on cowbird.com. It is as powerful now as it was then and fits nicely into this segment of Fragments. I appreciated so much about this section, and your writing, particularly this passage: "the way for me to navigate this strange experience was simply to 'live in its question' without trying to collapse or define it."

Thank you. As always. I look forward to catching up with your interview on Stoa.